Have you ever wondered what makes billions of IoT devices communicate seamlessly across the globe?

"The global cellular IoT module market, with annual shipments amounting to 514 million units in 2024, is expected to reach 866 million units by 2029, growing at a CAGR of 11%." - Berg Insight

As connected devices multiply across industries, a key question emerges: how do these sensors, controllers, gateways, and cloud applications exchange information reliably and at scale?

To address this, it becomes essential to understand the interfaces and communication protocols that underpin modern IoT and embedded systems. These hardware links and data-exchange standards determine how devices transfer information, synchronize operations, and support the automation and intelligence expected in today's connected environments.

IoT interfaces and protocols represent the fundamental communication infrastructure that enables devices to exchange data, coordinate operations, and integrate into larger intelligent systems. These IoT protocols carry digital signals between sensors, processors, networks, and cloud systems.

But here's the million-dollar question: With so many communication options available, how do engineers choose the right interface for their IoT projects?

The answer lies in understanding the fundamental hardware interfaces, such as I2C, SPI, and UART, for local device communication and wireless protocols like LPWAN, NB-IoT, and 5G for wide-area connectivity. Each serves a specific purpose in the IoT ecosystem, much like different languages serve different communities in our global society.

Why are hardware interfaces and protocols important in IoT hardware design?

In any embedded or IoT system, interfaces form the physical and logical links that let sensors, controllers, radios, and peripherals exchange information. Whether it is a GPIO line, a high-speed SPI bus, or a wireless transceiver, each interface determines how accurately and efficiently an IoT device can communicate with the rest of the system. Software-level interfaces then build on top of these electrical connections, defining how applications interpret, manage, and route the data coming from underlying hardware.

Together, these interfaces and communication protocols establish the rules for:

- how devices join and interact within an IoT network

- what signalling methods and data formats are used during communication

- how transmission errors or faults are detected and resolved

- what protections secure data as it moves between components

- how power usage is managed in battery-driven or low-energy devices

Because modern IoT architectures span everything from hardware buses to cloud-based services, multiple layers of interfaces and protocols work in parallel to keep data moving reliably through the entire system.

What are Hardware Interface Architectures?

Hardware Interface Architectures refer to the structured designs and protocols that define how different hardware components of IoT communicate, connect, and interact with each other within a computer system or electronic device. This IoT architecture establishes the rules, standards, and physical/ logical pathways for data exchange between various hardware elements of IoT.

Key Components of Hardware Interface Architectures

The physical layer, protocol layer, and logical layer form the main components of hardware interface architecture.

Physical Layer

The physical layer in IoT architecture includes connectors, cables, pins, and electrical specifications that define how hardware components of IoT physically connect. This encompasses voltage levels, current requirements, signal timing, and mechanical form factors.

Protocol Layer

The communication protocols in the protocol layer of IoT architecture define how data is formatted, transmitted, and received across major components of IoT. It includes addressing schemes, error detection/ correction methods, flow control mechanisms, and synchronization protocols.

Logical Layer

The logical layer in this IoT architecture forms an abstract representation of how software and firmware interact with hardware interfaces, including device drivers, APIs, and abstraction layers that simplify hardware complexity for higher-level applications.

Common Types of Hardware Interface Architectures

Modern IoT and embedded systems rely on a wide range of hardware interface architectures to move data between components. These include traditional bus systems, legacy parallel interfaces, high-speed serial links such as USB or Ethernet, and short- or long-range wireless communication options like Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, or cellular technologies. Although parallel interfaces have played a historic role, most contemporary designs use serial and wireless connections because they offer better performance, simpler routing, and improved noise immunity.

Bus Architectures

Bus-based architectures-such as PCI, PCIe, and system buses-have long been used to interconnect processors, memory, and peripherals. These shared communication pathways are still relevant in many systems, but modern embedded designs increasingly adopt dedicated, point-to-point serial links to reduce latency and avoid electrical contention across devices.

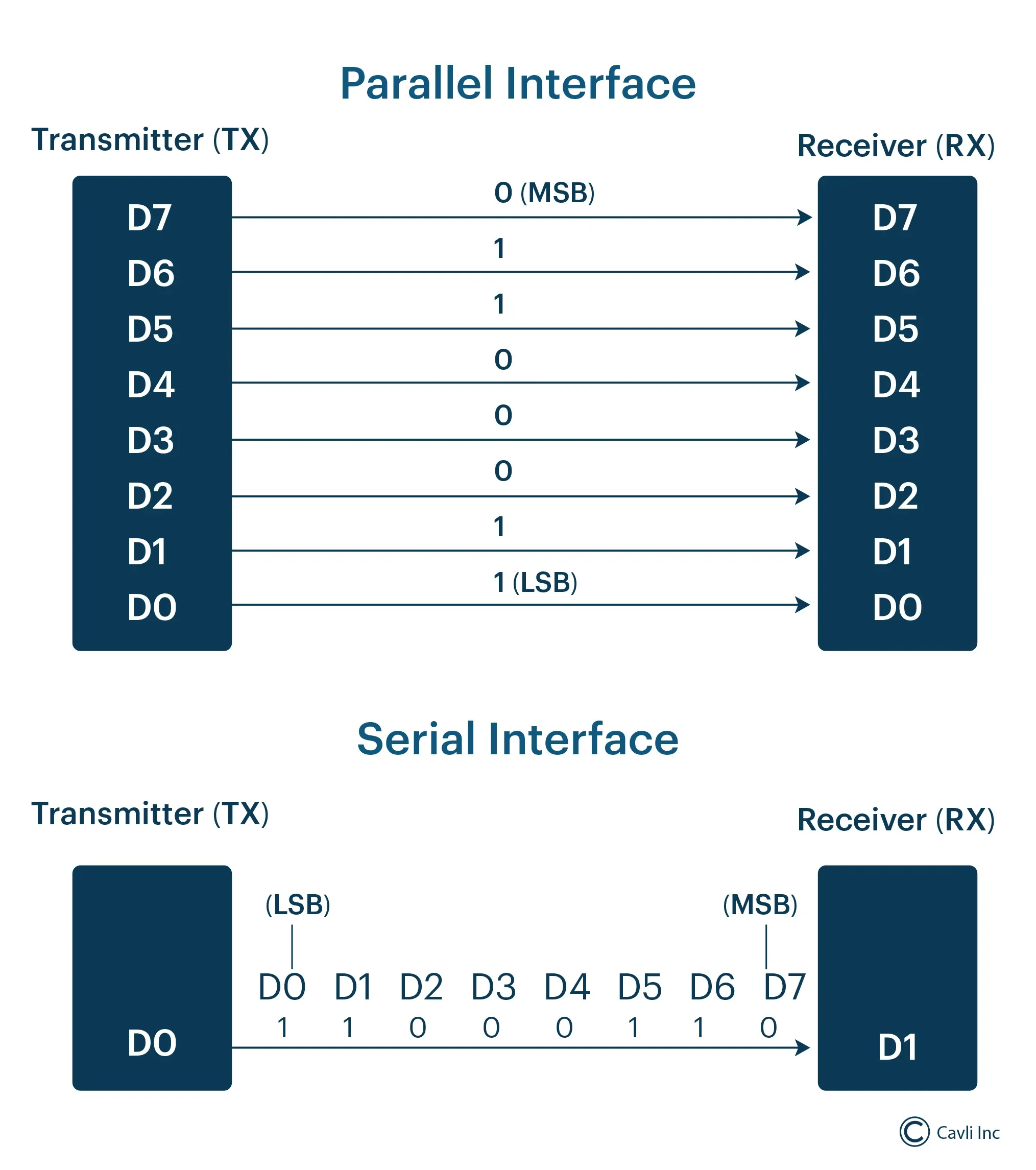

Parallel Interfaces

Parallel interfaces transmit multiple bits simultaneously through separate conductor lines. While once widespread, they are now used far less frequently due to timing skew, synchronization challenges, and difficulty maintaining signal integrity at higher clock rates. Their role has largely been replaced by compact, high-bandwidth serial interfaces.

Serial Interfaces

Serial communication architectures like USB, SATA, and Ethernet transmit data a single bit or symbol at a time across fewer conductors. These interfaces reduce board complexity and electromagnetic interference while supporting high transfer speeds. As a result, serial links have become the default choice for most embedded and IoT hardware designs.

Wireless Interfaces

Wireless communication layers-including Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, and cellular technologies-provide connectivity without physical wiring. These interfaces are essential in IoT devices that require mobility, remote placement, or integration across distributed systems.

IoT Hardware Design Considerations

Designing hardware for IoT applications involves balancing power efficiency, data throughput, timing constraints, robustness, and long-term reliability. Interface selection impacts system performance, device lifetime, and scalability. Architectures continue to evolve, targeting higher speeds, lower power consumption, and tighter integration between processing, storage, and connectivity blocks.

Performance Requirements

The bandwidth, latency, and throughput required depend on the application-from low-data-rate sensor networks to high-speed edge computing systems. Each interface must be selected to match the expected communication load and environmental conditions.

Power Management

Many modern interfaces incorporate power-saving features such as voltage scaling, low-power idle states, and optimized power delivery. These mechanisms help battery-powered IoT devices operate longer between charge cycles or maintenance intervals.

Scalability and Modularity

A modular hardware architecture allows future expansion and the addition of new peripherals or upgraded modules without redesigning the full system. Scalable interface choices help developers support evolving product requirements.

Reliability and Error Handling

Stable system performance depends on robust error detection and correction methods. Interfaces designed for noisy or electrically harsh environments use additional checks to maintain data integrity and avoid communication faults.

Hardware interface architectures continue to advance as embedded systems demand higher transfer speeds, greater efficiency, and denser integration. A solid understanding of these architectures allows designers and engineers to develop systems that remain functional, adaptable, and reliable over long lifecycles.

Fundamental Hardware Interfaces Used Across IoT Applications

IoT devices integrate a wide spectrum of hardware interfaces-from short-range serial links like SPI, I2C, and UART to industrial standards such as RS-485, CAN, and Modbus. Debug ports (JTAG, SWD), power delivery interfaces (USB-PD, PoE), and location-tracking protocols (NMEA, RTCM) also play important roles in device configuration, power management, and geolocation.

Serial Communication Interfaces

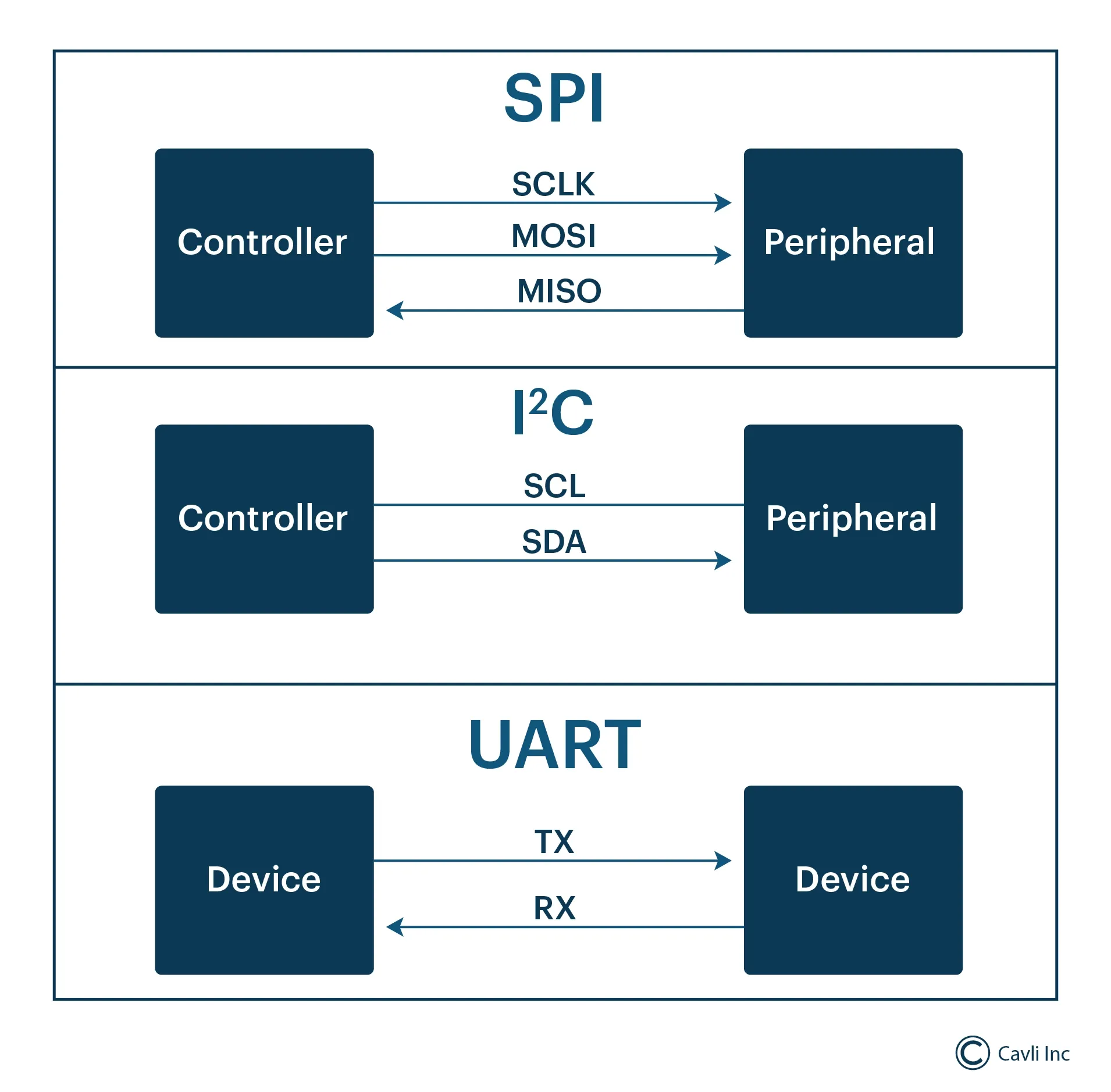

Serial Peripheral Interface (SPI)

SPI is a synchronous, full-duplex communication bus used for short-distance exchanges between microcontrollers and peripherals. Its dedicated lines for MISO, MOSI, clock, and chip select allow high-speed, low-latency operation in devices like sensors, displays, and memory chips.

Inter-Integrated Circuit ( I2C)

I2C is a synchronous, two-wire protocol intended for connecting integrated circuits on the same board. It supports multi-master configurations and uses addressable devices, making it practical for sensors, EEPROMs, and real-time clocks in compact IoT designs.

Universal Asynchronous Receiver/Transmitter (UART)

UART handles asynchronous serial communication by converting parallel data into serial form and vice-versa. It remains a widely used interface in embedded systems for modules such as GPS receivers, Bluetooth radios, and diagnostic ports.

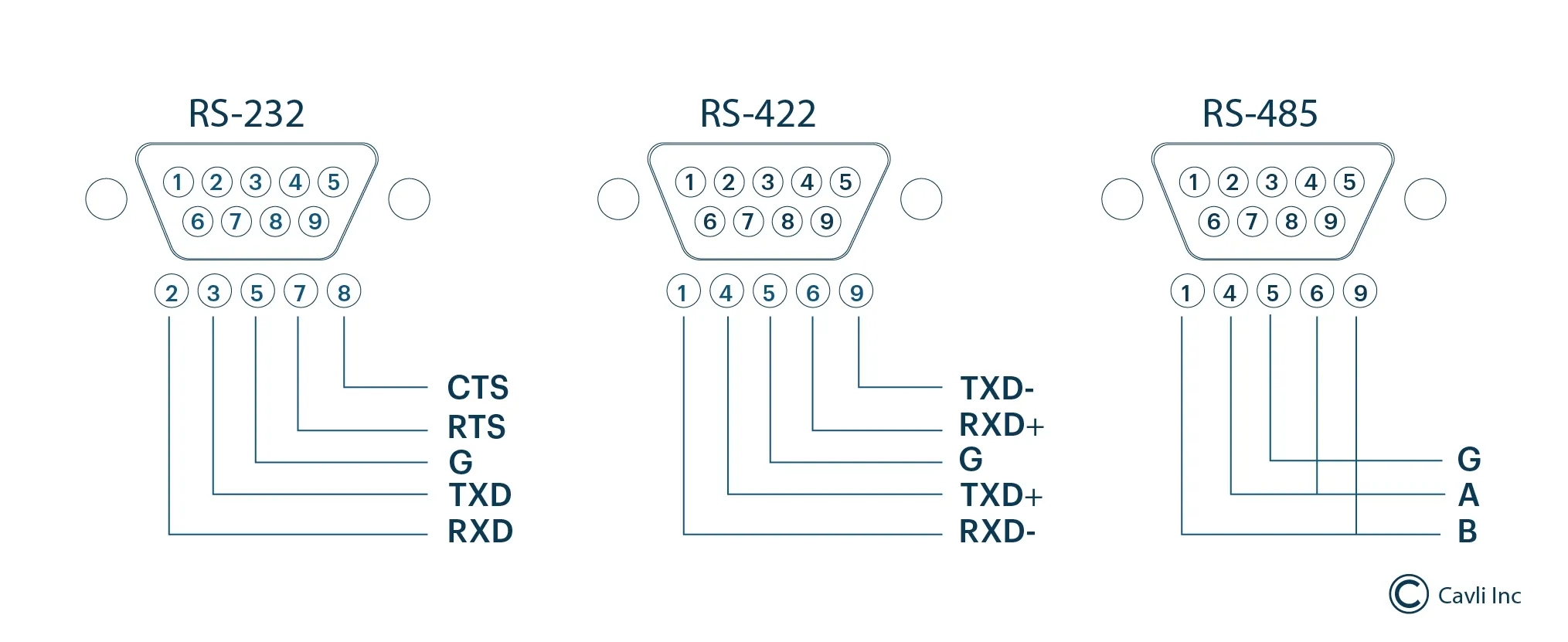

Recommended Standard 232 (RS-232 )

RS-232 is a legacy single-ended interface used for point-to-point asynchronous communication. Though limited in distance and speed, it still appears in specialized equipment and industrial consoles.

Recommended Standard 422 (RS-422)

RS-422 enhances RS-232 by using differential signaling to support longer ranges and higher data rates. It is common in industrial instrumentation where noise reduction is essential.

Recommended Standard 485 (RS-485)

RS-485 uses differential signaling to support multi-point networks in harsh electrical environments. It is widely adopted in building automation, industrial control, and long-distance data acquisition systems.

Process Field Bus (PROFIBUS)

PROFIBUS is a deterministic fieldbus protocol used in real-time industrial automation. Built on RS-485 physical layers, it supports cyclic and acyclic communication between controllers and field devices.

Modbus RTU/ASCII

Modbus enables master-slave communication across serial networks. RTU frames binary data for compact efficiency, while ASCII mode uses printable characters for easier debugging.

Controller Area Network (CAN Bus)

CAN is a message-based, multi-master protocol designed for high-reliability communication in electrically demanding environments. It prioritizes messages by identifier and is widely used in automotive and industrial systems.

DeviceNet

DeviceNet extends CAN by adding a higher-level network protocol used in automation systems. It enables distributed control and supports communication and power delivery over the same cabling.

Local Interconnect Network (LIN Bus)

LIN is a cost-effective serial protocol supporting simpler automotive subsystems such as door modules and HVAC controls. It complements CAN by handling lower-speed devices.

Highway Addressable Remote Transducer (HART)

HART overlays digital signaling on top of a 4–20 mA analog loop. It allows configuration and diagnostics without disrupting the underlying analog measurement.

Serial Data Interface at 1200 baud (SDI-12)

SDI-12 is a low-power, multi-drop serial interface designed for environmental monitoring sensors requiring long cable runs and minimal consumption.

Digital Multiplex 512 (DMX512)

DMX512 is used for lighting control and stage effects. It sends continuous frames over twisted-pair cabling to coordinate dimmers, color units, and lighting fixtures.

Digital Addressable Lighting Interface (DALI )

DALI is a bidirectional lighting control protocol allowing individual addressing and feedback for lighting fixtures. It is commonly used in building automation to enable energy-efficient lighting management.

Debugging and Programming Interfaces

Joint Test Action Group (JTAG)

JTAG is a long-standing industry standard used to test, program, and debug embedded hardware such as microcontrollers, FPGAs, and SoCs. It gives engineers low-level access to device internals, supports boundary-scan diagnostics, and is widely used during development and device bring-up to ensure hardware reliability and accurate firmware loading.

Serial Wire Debug (SWD)

SWD is ARM's compact, two-wire alternative to JTAG, designed for Cortex-M microcontrollers. It preserves full debugging capability while reducing pin count-an advantage in space-constrained IoT hardware. SWD is commonly used for firmware development, real-time debugging, and production programming of ARM-based devices.

In-System Programming (ISP)

ISP allows microcontrollers to be programmed directly on the assembled PCB without removing them. It is widely used to update firmware during development and to push maintenance updates in deployed IoT devices, enabling efficient field servicing and version control.

In-Circuit Serial Programming (ICSP)

ICSP is Microchip's dedicated interface for programming PIC microcontrollers. It supports both debugging and firmware flashing, making it essential for PIC-based IoT modules used in sensors, consumer devices, and industrial controllers.

Program and Debug Interface (PDI)

PDI is Atmel's interface for programming and debugging AVR microcontrollers. It provides reliable access for firmware development, production flashing, and maintenance updates across many low-power IoT devices using AVR cores.

aWire/debugWIRE

aWire/debugWIRE is a single-wire programming and debugging interface for AVR microcontrollers. It is built for extremely compact boards where pin count is limited, enabling developers to debug and program small IoT devices with minimal hardware overhead.

Open On-Chip Debugger (OpenOCD )

OpenOCD is an open-source toolchain supporting a wide range of debug adapters and protocols, including JTAG and SWD. It is often used in IoT firmware workflows to connect with various microcontrollers, providing a flexible and cost-effective debugging ecosystem across heterogeneous hardware platforms.

Embedded Trace Macrocell (ETM )

ETM is an ARM technology that records real-time instruction and data traces without disturbing program execution. Engineers rely on it for profiling, timing analysis, and tracking down complex firmware issues. ETM is valuable in IoT systems requiring deterministic performance and detailed insight into runtime behavior.

CoreSight

CoreSight is ARM's advanced debug and trace architecture that integrates components such as ETM, DWT, and TPIU. It provides deep visibility into code execution, enabling developers to diagnose subtle firmware issues, analyze performance bottlenecks, and strengthen system security in sophisticated IoT devices.

Power and Energy Management Interfaces

USB Power Delivery (USB PD)

USB PD offers scalable voltage and current delivery over USB cables. IoT gateways, smart hubs, and compact edge devices often rely on USB PD to negotiate power profiles dynamically, supporting fast charging and intelligent power distribution across multi-rail systems.

Power over Ethernet (PoE)

PoE transmits electrical power alongside data through standard Ethernet cables. It simplifies deployment of IP cameras, access points, building-automation sensors, and other IoT devices by eliminating the need for separate power wiring. PoE supports centralized power management and improves reliability in large installations.

System Management Bus (SMBus)

SMBus is a two-wire protocol tailored for communication between batteries, power controllers, and embedded management units. It enables real-time reporting of battery status, thermal conditions, and health metrics, making it an essential component of power-optimized IoT systems.

Fuel Gauge Interfaces

Fuel gauge interfaces track battery state-of-charge, health, and discharge behavior. They are widely used in handheld IoT devices, wearables, asset trackers, and sensor nodes where accurate power monitoring is critical for predicting device runtime and optimizing energy use.

Power Management IC Interfaces (PMIC)

PMIC interfaces control voltage regulation, power sequencing, charging, and protection mechanisms. In IoT hardware, PMICs coordinate multiple power rails, ensuring stable operation across sensors, radios, and microcontrollers while maintaining efficiency in space-restricted designs.

Load Switching Interfaces

These interfaces manage power routing to individual hardware components. By selectively powering down unused peripherals, load switches reduce energy consumption and extend battery life-important for low-power IoT designs.

Power Monitoring Interfaces

Power monitoring circuitry measures voltage, current, and overall consumption in real time. Integrating these interfaces helps engineers diagnose power anomalies and refine energy-saving strategies, especially in battery-operated IoT devices.

Satellite and GPS Interfaces

National Marine Electronics Association 0183 (NMEA 0183)

NMEA 0183 is a serial protocol used by GPS and GNSS receivers to communicate position, time, and motion data to a host device. It is widely implemented in asset trackers, fleet-management units, navigation systems, and wearable location devices. Its structured, readable data sentences simplify parsing and allow seamless integration with embedded and IoT platforms.

RTCM (Radio Technical Commission for Maritime Services)

RTCM is a protocol for transmitting real-time differential GPS (DGPS) correction data, which enhances the accuracy of GNSS positioning. It facilitates centimeter-level accuracy (such as Real-time Kinematics) in applications such as surveying, agriculture, autonomous vehicles, and drone navigation. RTCM defines the rules and data formats for differential corrections sent to improve the accuracy of GNSS data.

Interfaces Used in Specific IoT Use Cases

IoT applications use specialized interfaces tailored to their domains-ONVIF, RTSP, and PoE+ in smart surveillance; LonWorks and DALI in smart buildings; EtherCAT and IO-Link in IIoT; Modbus and DNP3 in smart grids; CAN-FD and MOST in automotive clusters; ISO protocols in OBD; and FPD-Link, GMSL, and LiDAR in ADAS. Here is the breakdown of interfaces according to the specific applications.

Smart Surveillance

Smart surveillance blends video monitoring with AI, machine learning, and edge analytics to interpret activity as it happens. These systems rely on industry-standard interfaces such as:

- Open Network Video Interface Forum (ONVIF)

- Real-Time Streaming Protocol (RTSP)

- Power over Ethernet Plus (PoE+)

- Alarm I/O

- Audio I/O

Together, these interfaces allow cameras and sensors to exchange real-time video, event alerts, and control signals. Modern surveillance platforms use computer vision to track motion, classify objects, recognize faces, and detect unusual behavior automatically. With predictive analytics and integration into wider IoT deployments, they support applications in retail, transportation, public safety, and city infrastructure.

Smart Building

Smart building and HVAC systems tie together ventilation, lighting, air-conditioning, occupancy tracking, and energy automation. They operate through established communication interfaces such as:

- Local Operating Network (LonWorks)

- Energy Harvesting Wireless Technology (EnOcean )

- Digital Addressable Lighting Interface (DALI)

These technologies help buildings adjust environmental controls automatically based on usage patterns, time schedules, and sensor feedback. Remote management, automated rule-based control, and real-time diagnostics allow facilities to improve energy efficiency and enhance occupant comfort.

Industrial IoT (IIoT)

IIoT environments connect machinery, sensors, and control systems to capture operational data, monitor performance, and automate industrial processes. Common interfaces enabling this ecosystem include:

- Ethernet for Control Automation Technology (EtherCAT )

- POWERLINK

- Industrial Input/Output Link (IO-Link)

These protocols support deterministic communication, high-speed control loops, and distributed sensing. IIoT is widely used in smart factories, asset tracking systems, energy monitoring, and predictive maintenance workflows.

Smart Grid

Smart grid solutions integrate IoT sensors, metering infrastructure, and utility management systems to modernize power distribution. They commonly employ:

- Modbus Remote Terminal Unit / Transmission Control Protocol (Modbus RTU/TCP)

- Distributed Network Protocol Version 3 (DNP3)

These protocols help coordinate real-time grid monitoring, demand management, and renewable energy integration. Two-way communication between utilities and consumers improves power reliability, reduces outages, and supports distributed resources such as rooftop solar.

Automotive Clusters

Automotive instrument clusters combine digital displays with in-vehicle networks to deliver information such as speed, engine status, navigation, and alerts. Interfaces used in modern clusters include:

- Local Interconnect Network (LIN)

- CAN with Flexible Data Rate (CAN-FD)

- Media Oriented Systems Transport (MOST )

These networks allow ECUs, sensors, and infotainment systems to communicate seamlessly. Contemporary clusters support driver-assistance notifications, personalization features, smartphone connectivity, and OTA updates, forming part of a broader connected-vehicle architecture.

On-Board Diagnostics

OBD systems monitor vehicle health, emissions, and performance through standardized diagnostic protocols. Modern OBD implementations use:

- International Organization for Standardization 14229 (Unified Diagnostic Services) ISO 14229 (UDS)

- International Organization for Standardization 14230 (Keyword Protocol 2000)ISO 14230 (KWP2000)

- Society of Automotive Engineers J2534 (Pass-Thru Vehicle Programming Interface) (SAE J2534)

Through an OBD-II port, technicians and diagnostic tools can access real-time engine data, fault codes, fuel metrics, and emissions information. These interfaces also support predictive maintenance and remote diagnostics in connected-car applications.

Advanced Driver Assistance Systems

ADAS platforms rely on a suite of sensors-cameras, radar, LiDAR, and embedded AI-to interpret road conditions and assist drivers. The specialized interfaces used for high-bandwidth sensor data include:

- Flat Panel Display Link III/IV (FPD-Link III/IV)

- Gigabit Multimedia Serial Link (GMSL)

- Automotive Physical Layer Interface (A-PHY)

- Automotive Radar Interfaces

- Light Detection and Ranging Data Interfaces (LiDAR)

These links carry high-resolution video and sensor streams with low latency, enabling features such as lane-keeping, blind-spot detection, adaptive cruise control, and autonomous parking. ADAS systems operate continuously, analyze potential hazards, and trigger alerts or corrective actions, forming the foundation for higher levels of vehicle autonomy.

Conclusion

Hardware interfaces form the backbone of IoT ecosystems. They define how sensors, processors, and communication modules interact, ensuring smooth data flow across diverse environments-from industrial plants and smart buildings to vehicles and healthcare systems. Selecting the right interface influences energy efficiency, latency, compatibility, and overall system reliability. As IoT deployments expand across industries, standardized interfaces remain essential to avoid fragmentation and to maintain interoperability. These communication pathways ultimately enable the intelligent, secure, and scalable IoT solutions powering today's connected world.